Frank Lloyd Wright’s Leaded Glass

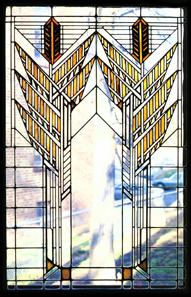

No other architect or designer of the modern era transformed the use of leaded glass in architecture as Frank Lloyd Wright. Creating ribbons of uninterrupted glass casement windows and doors in his Prairie style buildings, Wright conceived his windows as an integral part of his organic design. Known for their extensive use of clear glass with touches of color, the glass designs are all geometric abstractions unique to each building for which they were created. Wright called them “light screens.”

The sources for Wright’s glass designs range from the Froebel gifts of his childhood to Louis Sullivan’s flat ornamentation, to the designs of the Vienna Secession. But it was Japan that dominated Wright’s early aesthetic – the flat areas of color enclosed within black lines in the Japanese prints that he admired and the way in which the sliding shoji screens of indigenous Japanese architecture unite exterior and interior space. Wright stated, “I was working away at the wall as a wall and bringing it towards the function of a screen, a means of opening up space.”

Wright’s light screens illuminated his interiors with natural light, touched by the autumnal dashes of his color palette and animated by his exquisite visual geometries. Wright’s buildings follow the geometric principles he imposed on each project, and his glass designs also express the geometry that unites the building.

Between 1885 and 1923, when he stopped using leaded glass, Frank Lloyd Wright designed 163 buildings – of which 97 were constructed – that included leaded glass of his own design. Among Wright’s most significant glass programs from the era of his Oak Park Studio are the Ward W. Willits House (1902-03), Susan Lawrence Dana House (1902-04), Darwin Martin House (1903-05), Unity Temple (1905-08), Avery and Queene Ferry Coonley House (1908) and Coonley Playhouse (1912), and Frederick C. Robie House (1908-10).

Robie House was Wright’s last and greatest Prairie style house and includes some of his best-known windows. Wright designed 175 doors and windows for Robie House of which 163 original casements remain in the house today. The living room and dining room of Robie House are visually united into one continuous space by a 47-foot span of 24 leaded glass casement doors opening to a narrow balcony that extends across the length of the south façade. Wright’s window designs were a primary feature of his Prairie style, an expression of his creative intelligence, prolific imagination, and passion for beauty.

Subsequently Wright’s more vibrantly colored window designs for the Coonley Playhouse (1912), Midway Gardens (1913-14), and Emil Bach House (1915) reflected his exposure to contemporary modernist art movements such as Orphism and Synchromism. Hollyhock House (1919-21) was the last project for which Wright designed a complete program of leaded glass.